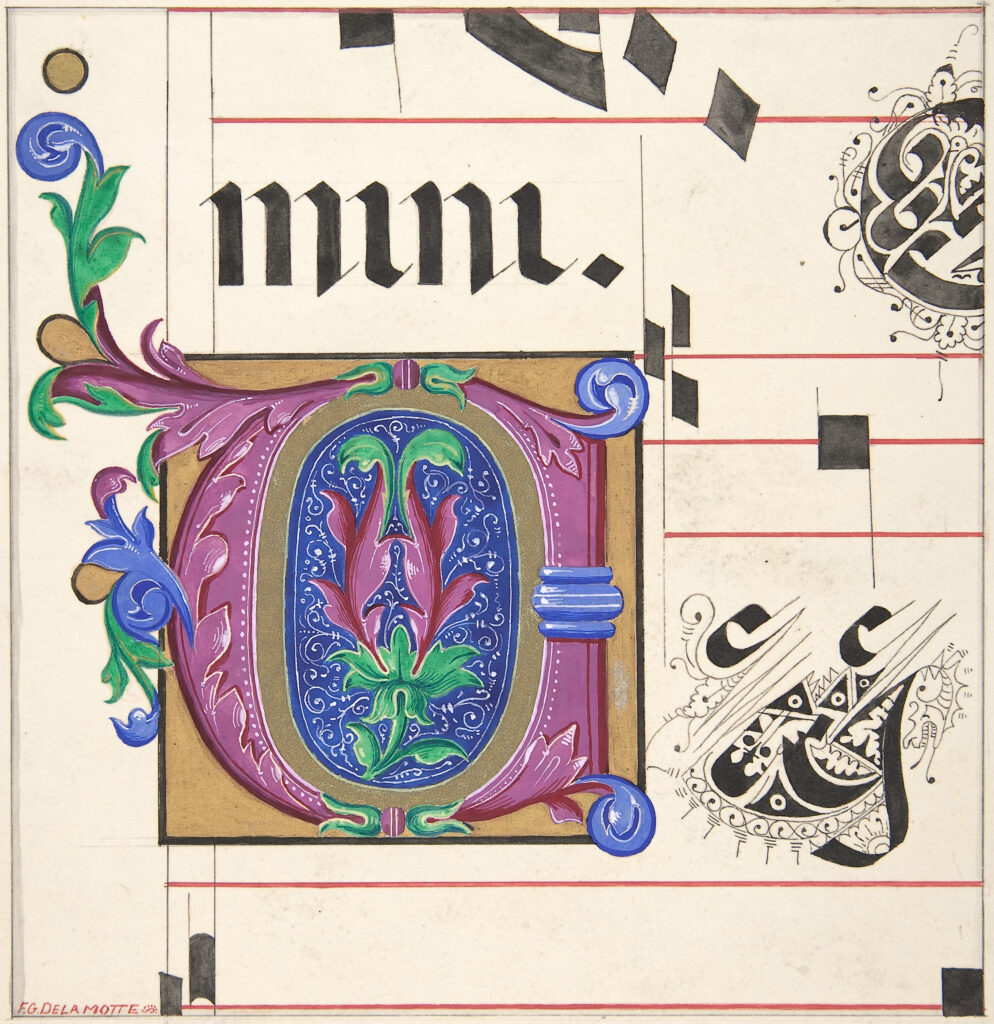

Freeman Gage Delamotte, Illuminated Initial from Hymnal, 1830–1862. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1966. Public domain.

1. Before my mum died I was a rain guy. Weren’t we all? Now I get it: the wind. Its shoulders. Smooth and deep as a bowl. Like a lullaby about a big old brush. Glowing, of course, but on the inside, far away from our world. Who could possibly go through the death of their mother and come out the other side anything less than a total idiot for wind? It is the golden whistle. God’s first attempt at a dinosaur. A holiday from all that silence and color.

2. In her final text messages, sent the night before she died, my mum invites her friend over for sex, a reminder that two things can sometimes meet the same need.

3. The invitation to sex in the midst of death is my mum at her most desperate, so it’s also my mum as I most love her, miss her. Like the embroideries she made of my stepdad’s poems when he was dying of cancer, it weaves together death and love into something that can be shared, a made thing amid all the unmaking.

4. My mum always had a needlework going, though she called them her tapestries. Big old castles were a particular specialty. So were grumpy bowls of fruit. But what I remember most about her tapestries are the backs, that mess of colored thread that looks like a vomited version of the castle or sunset or pineapple on the front. When you live with a tapestry maker (tapestrist? tapestreur?) you get used to seeing this frayed mass of color, which they carry around with them at all times like a small shield. The hours my mum spent tapestrating appeared to be spent inspecting the reverse of a mysterious hairy object.

5. She had a funny idea of fun, my mum. As a librarian and schoolteacher, she had a habit of parceling off excitement into manageable packets called “activities.” We didn’t “do stuff,” we completed “projects.” She treated fun as something that needed to be safeguarded, as though there were only so much of it. Or as though it were something there was only one of, like a library book that had to be returned before it could be borrowed again. As one of four children, I seemed to spend a lot of time waiting for permission to access fun, which was always on hold somewhere else, or stuck in some administrative hinterland between borrowings.

6. I felt this frustration all the way into my twenties, but by then the frustration had moldered into contempt. I was ashamed of her for making fun unfun. I was embarrassed by her difficulty being happy. What I failed to understand is that my mum’s librification of fun had been a compromise. Like so many mothers, she was the scaffold upon which other people’s pleasures secretly depended. By organizing her fun, she was trying to protect it from the corroding forces of everyone else’s chaotic enjoyment.

7. After David died I watched Mum flourish through a kind of second adolescence. She colored her hair, bought a guitar, went traveling. On New Year’s Eve she emailed to say she was staying in an Ecuadorian “jungle lodge.” A few weeks later she wrote again to let us know she was “on a bus to the Grand Canyon.” Finally she quit her job and announced that she was leaving the UK for good. She was moving to a small, treeless island off the southern coast of Argentina, where there are more penguins than people. In our conversations it was always this odd fact about the penguins that she emphasized.

8. I think perish is a very beautiful word. She has perished. This bag contains perishable items. At its root the word means literally “to go through.” In the nineteenth century people used the form perisher, which meant either a person who destroys or a person who is destroyed. They couldn’t decide. When someone killed someone, they were a couple of perishers, but one of them had drawn the short straw. When I hear perish I picture a crate of Spanish oranges in the sun. Then I see a magician pulling threaded handkerchiefs from his sleeve. Then I hear parish, and I imagine a vicar eating a really juicy orange, with the juice dripping onto his shiny black vicar shoes.

9. A couple of months after Mum died I received a text from an unknown number. It was from a woman called Jo. She said she was Mum’s best friend in college, but they’d lost touch. She’d heard about her death and felt confused, wanted to understand. I deleted the message.

10. I’ve already done the work of forgetting the day we scattered her ashes, so I couldn’t tell you where they ended up. I don’t remember who went first, or how many fistfuls we got out of her. I vaguely remember someone tapping out the dregs like sand from their shoe.

11. In 1847 Kierkegaard writes in his diary, “Being trampled to death by geese is a slow way to die.” It turns out he’s upset because people keep on saying nasty things about his trousers.

12. In the years after Mum’s death something happened to my reading. In short, it stopped. I realized I hated reading, and that I had always hated it but had pretended to like it for social reasons. Now I saw clearly. Books are stuffy and ludicrous. Full of quotations from other books, and people saying simple things in confusing ways because they want to be loved but aren’t sure how.

13. When you’re happy, you don’t sit down and write about the stars or the mountains or whatever it is you love. You go out and be with them, in them. That’s why there’s no such thing as a happy book. A book is always about the world, and happy people don’t have time for “about.”

14. Through writing, if you’re lucky, you discover the importance of not writing. Reading, when it’s done well, is a lesson in the importance of not reading—that is, in living. A writer’s highest achievement, which is also the reader’s, is to fucking stop.

15. Only once have I put a book I was reading in the bin. It was Ted Hughes’s Rain-Charm for the Duchy, which collects the poems he wrote as poet laureate—never a promising period in a poet’s career. There is something uniquely awful about destroying someone else’s book. Saying no to it so thoroughly. Or not even destroying it: we put things in the bin we don’t care about enough to destroy. And it was a public bin, next to a bus shelter, which I imagine only adds insult to injury. To be fair, they were terrible poems.

16. A few months before she died my mum sent me an email saying she was reading D. H. Lawrence’s The Virgin and the Gypsy and Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton. There’s only one bookshop on the island, she says, and its selection is “somewhat bizarre.” I haven’t read either of those books, but I just found the Lawrence online. It appears to be about a woman who leaves her husband and children. The opening page contains one of the strangest sentences I’ve ever read. “The ill wind that blows nobody any good swept away the vicarage family on its blast.”

17. The last time I saw my mum was at a Mexican restaurant in a shopping mall. It was happy hour, and we were having drinks and tacos. My brother, my sisters, my mum, and me. Her visits home had become fewer and farther between, but we were all together for once. After a couple of glasses of wine she asked whether she had been a good mother. A poster on the wall by the bar said “Life always needs a little salsa.” I said I didn’t know. I said the trouble with mothers is you only get one, so it’s impossible to say whether yours is good or not. I regret it every day.

18. I walk around with a chest inside me. It’s buried, like all good chests, and full of air, like all bad ones. My hands look naked and amazed. They unlock doors and go in. They scissor light. I can feel the wind from the window in the openings between my fingers. We have to love our way through it, this life. This luckiness. In a moment it’s going to stop being almost 5 p.m.

19. Nowadays I take a lot of supplements. One of them is called choline and it helps you think better. Another is D3, which helps you not to be sad. I take these together and swoon, sort of inside myself, at the amazing victory of it. If you’re going to be clever you had better be happy too, otherwise why bother.

20. Another one I take, but less often, contains tons and tons of bacteria. Usually Vala and I take it together, and we wonder what all the bacteria who are already inside us think about it. One of the pleasures of taking a probiotic, it seems to me, is the experience of putting billions of things inside yourself at once. You feel like you must be breaking some kind of record. But then you remember atoms. And protons. And the way a single mozzarella stick contains, god knows, a trillion quarks? And the dream crumbles. I guess we’re always putting billions of something inside us, but it’s the knowing that makes it weird. If the front cover of this Walmart ready-pour meat gravy advertised “billions of meat gravy atoms in every bite” I think that would be a game-changer for me.

21. Perhaps my favorite is the multivitamin. The one I take comes in a see-through capsule and inside it you can see lots of little white beads floating in a sort of golden plasma. Picture a snow globe but for a mouse, and instead of Christmas it’s your future but without any suffering. When you put that in you, you really feel like a million bucks.

22. It’s nice to outsource things like that. Knowing the snow is going on even while you make a sandwich. The world is so efficient because it doesn’t need you. It is in shock and emits a tree. It is a meaningless failure of rock and light.

23. In my earliest memory I’m standing next to Mum in the corner shop, in the village I grew up in. We’re at the till, by the door, and a man walks over, puts his things on the counter, and says to Mum, “I’d know those legs anywhere.” I must have been young because I’m holding on to her knee. She’s wearing sandals, so I guess it’s summer. But here the memory fizzles out. I can’t picture the man’s face, but I can hear his voice very clearly, and it’s one of those voices where you can tell, without looking, based on a slight foxing of the sound around the edges, that it has passed through a mustache. Unless, of course, what time and mustaches do to sound is the same. But I don’t think that’s true.

24. When she was twenty my mum broke both her legs. She was on her way to visit my dad and drove her motorbike straight into the back of a parked truck. When I ask my dad, forty years later, what caused her to drive into the back of a truck, he says it was raining and there were raindrops on her glasses.

25. Seneca says we can’t choose our parents, but we can choose whose children we want to be.

26. At 4 P.M. on Friday, October 24, 2014, the afternoon before she died, my mum drove to the island hardware store and bought a handful of disposable grills. She was served by Olivia, and the transaction took place at 4:44. My mum seems to have been plagued by fours that day. In her witness statement, the till girl says she has tried to picture the person she sold the grills to but can’t. Then she asks the policeman whether this is about the teacher she read about in the paper, and he says it is.

27. “Almost from prehistoric times, the number four was employed to signify what was solid, what could be touched and felt. Its relationship to the cross (four points) made it an outstanding symbol of wholeness and universality, a symbol which drew all to itself.”

28. In China the number four is distrusted because of its similarity to the word for death.

29. In her final week, on the way to the swimming pool, my mum asked her friend how they would kill themselves. She’d read online that the “fashionable” way to do it was to light a few single-use grills in your bedroom and seal yourself in. She and her friend joked about what they’d cook on the grills while they were dying. It’s a good joke, I think. “I’m afraid I have some terrible news. Terrible, fingerlickin’ news.” I like it more and more as time goes by. Even in her darkest hour, her sense of humor remained intact. When she died, she was still herself. It makes it worse and better. It means she truly chose it. And it means she truly chose it.

30. When we were kids, my friend Jon and I played a game in which we yelled goodbye to each other at increasing distances on our separate walks home. We lived about a mile apart. I could still just about make out Jon’s voice at the top of my road. But at some point along the way I had become, at least from the point of view of our worried neighbors, a child screaming goodbye to no one.

31. They dug up a time capsule at a school in New York today. I read about it on the news. Students at the school were asked to write predictions of what would be found inside. The school’s principal unsealed the capsule during a live streamed ceremony. There were trombones, and the principal read aloud some of her favorite predictions. Finally she unsealed the capsule, which was filled to the brim with mud.

Luke Allan is the editor of Oxford Poetry and the author of Sweet Dreams, the Sea, forthcoming from the Poetry Society of America in 2025. This piece is adapted from a book-length work in progress, titled “The End.”