The Christmas season is all about celebrating the joys of life, and what’s more joyful than dessert? But just where do Christmas desserts come from? And how did they become part of the holiday season?

Here’s a handy guide to some of the most delicious traditional Christmas desserts that you might not have heard of – and the fun part: where you can try them yourself.

1. Taste kahk in Egypt

In Egypt, making kahk (cookies) is a custom as old as the pharaohs. Drawings of women making kahk have been found on the walls of Pharaonic temples in the ruins of Thebes and Memphis.

In ancient times, kahk were often stuffed with dates and figs. Today, the shortbread-like cookies, imprinted with a geometric pattern, are made with a variety of stuffings – dates, pistachios, walnuts – or spiced with cinnamon, cloves and ginger, and sometimes also fennel seeds, anise seeds and mahlab (ground sour cherry kernels).

Kahk are enjoyed by both Muslims and Coptic Christians to mark the end of Ramadan and Advent fasting, respectively, as well as other festivals. Coptic Christians often bring a box of kahk as a gift when visiting friends and family at Christmas.

Where to try it: Zack’s Bakery Cafe or the legendary Khan Al Khalili bazaar, both in Cairo.

2. Savor bibingka in the Philippines

Bibingka is a type of sweet, glutinous rice cake commonly eaten during the Christmas season, which begins in September in the Philippines. The batter is traditionally poured into a terracotta dish lined with a banana leaf and steamed in a clay oven with coals above and below.

The sticky cakes were originally presented as offerings to gods or given as gifts to honored guests. Today, bibingka is still a special pleasure among Filipinos, who often have it for breakfast or right after a dawn mass during the holidays. The popular delicacy is also enjoyed in parts of Indonesia.

Where to try it: Cafe Via Mare in Manila.

3. Sample buñuelos in Mexico

These light, crisp, sweet discs are a beloved treat in Mexico during the holidays. A legacy of the Spanish colonists, buñuelos are made of fried dough sprinkled with sugar or soaked in piloncillo syrup (made from cane sugar). The precise recipe and shape vary from state to state. For instance, in Tabasco, people make a similar version to the original, while in Veracruz, they come in different flavors, such as sweet potato, pumpkin, or almond, and some are small balls or donuts fried in lard and dusted with sugar. In other Latin American countries, such as Colombia, buñuelos are ball-shaped and filled with cheese.

Where to try them: Street food stalls across Mexico sell buñuelos at Christmastime.

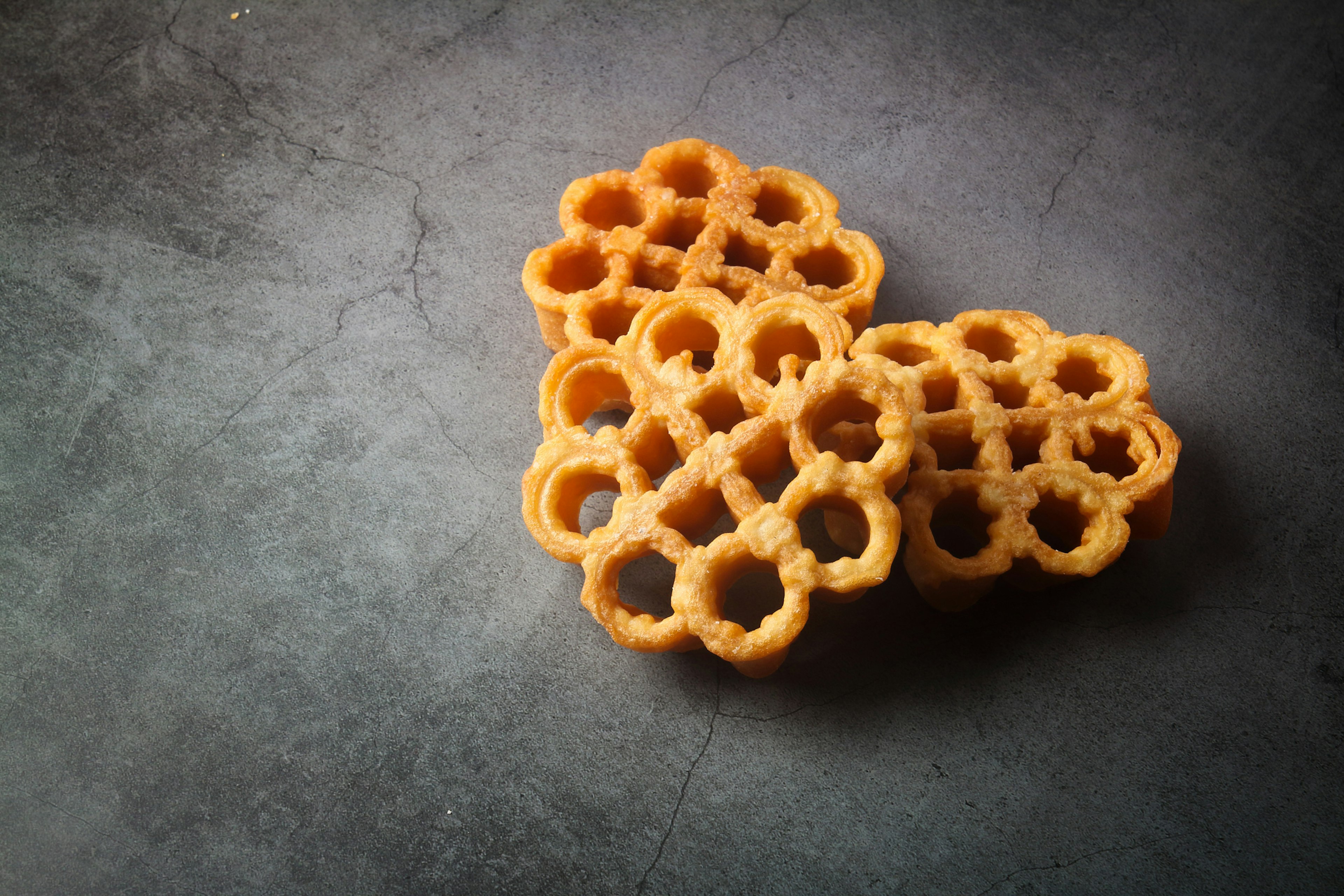

4. Snap up rose cookies in India

Rose cookies are especially popular at Christmas in the Indian state of Goa, which was subjected to Portuguese rule for almost 500 years. Known in Portuguese and Goan as rose de coque, they are not really cookies at all but rather fried dough infused with cardamom and vanilla. The rose shape is achieved using a cast iron mold with a rounded, flower-like design. After frying, rose cookies might be dipped in or sprinkled with icing sugar.

Where to try them: Nicolau Bakery in Raia, Goa.

5. Dig into malva pudding in South Africa

Malva pudding, or malvapoeding in Afrikaans, is a rich, sweet cake deeply rooted in South Africa’s Cape Dutch culture, and most popular in Cape Town. While not eaten exclusively at Christmas, its decadence means it’s reserved for special occasions. Also known as lekker (meaning delicious) pudding, the traditional dessert is prepared with apricot jam and a little malt or balsamic vinegar to give it a caramelized texture. Some variations include ginger, brandy, and/or Amarula liqueur. Once baked, and while still hot, the cake is drenched with a creamy sauce that sinks into it as it cools, transforming the cake into a deliciously sticky pudding.

Where to try it: De Oude Cafe and Restaurant or Willoughby & Co in Cape Town.

6. Try traditional stollen in Germany

This cake-like fruit and nut bread coated in icing sugar originated in Dresden, and its protected geographical status means only stollens made in or around the city by recognized bakers are considered genuine.

In the Middle Ages, stollen was a hard bread made of oats, flour and water that was eaten during the Advent fasting period. In 1490, however, the pope granted special dispensation for bakers to use butter and other rich ingredients such as raisins, marzipan and candied orange peel – foods that were forbidden during Advent – to make their Christmas bread. Around 1560, Dresden’s bakers began to present Saxony’s rulers with an enormous stollen every Christmas. In 1730, Saxon leader Augustus the Strong commissioned a stollen that could feed 24,000 people. The result is said to have contained 36,000 eggs and weighed a staggering 1.8 tonnes.

The mammoth stollen tradition continues today at the annual Dresden Stollenfest that takes place on the Saturday before the second Advent – which will be on December 7 in 2025.

Where to try it: At the Stollenfest or at Schlosscafé Emil Reimann which are both in Dresden.

7. Relish beigli in Hungary

This sugary, roll-shaped pastry containing a dense swirl of poppy seeds or walnuts is a Christmas fixture in Hungary. Beigli is a German-Yiddish word meaning “horseshoe” or “to bend,” and according to old folk traditions, walnuts protect against magic spells or curses, while poppy seeds, imported by the Ottomans, symbolize prosperity. Beigli’s cousin, flódni, is a Jewish-Hungarian dessert stacked with layers of apple, walnut, and poppy seeds.

The ubiquitous Christmas treat as it is known today came to Hungary in the second half of the 19th century, during the Austro-Hungarian empire. Initially baked only in the home as a family ritual, beigli eventually spread to cukrászdas, or confectionaries.

Where to try it: Christmas markets are the best place to try beigli. Alternatively, try it at Édeském Cukrászda, or on the festive menus of traditional restaurants like Rosenstein – both in Budapest.