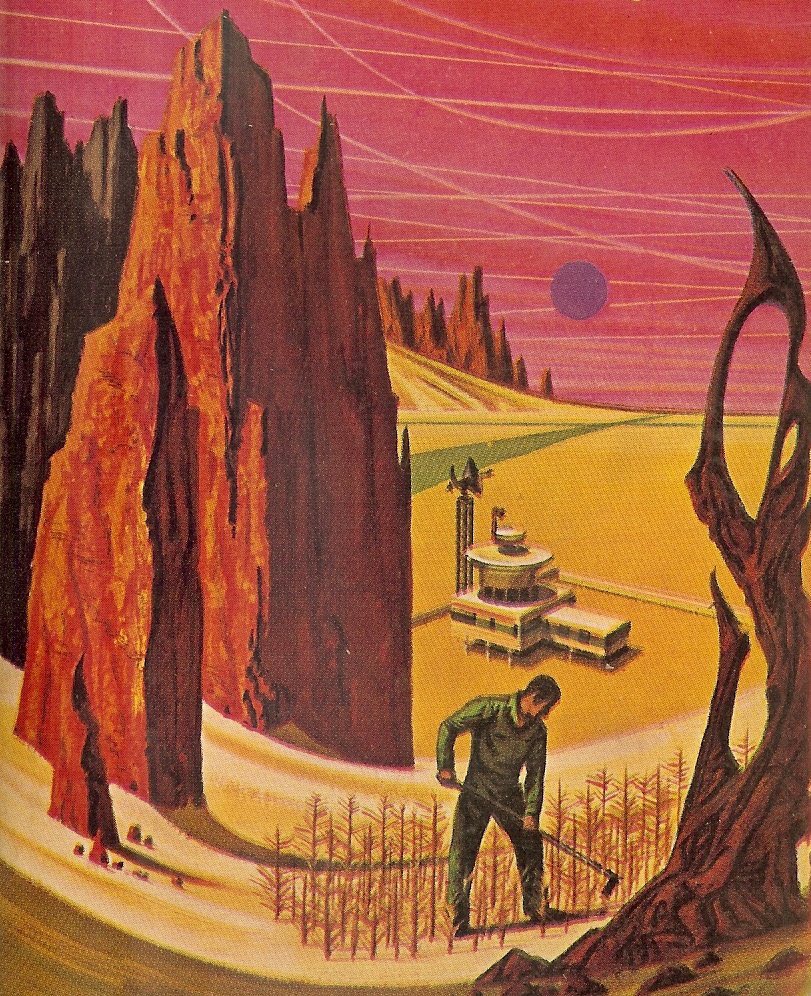

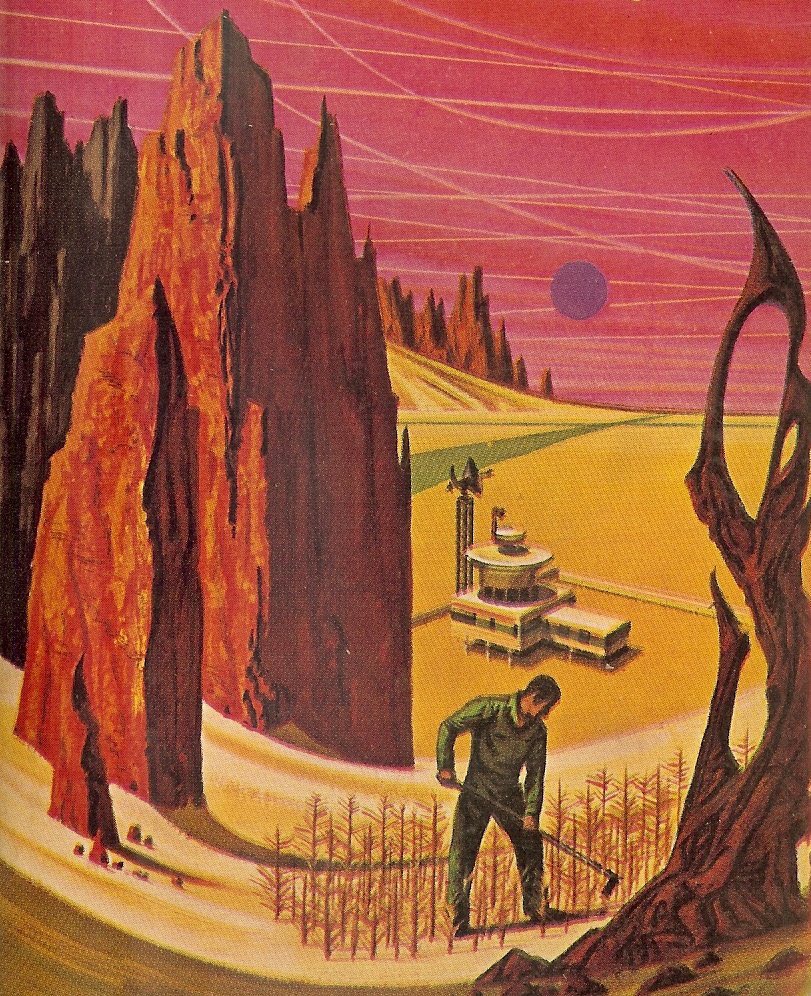

Detail from the cover art of the first edition of Martian Time-Slip (1964).

1.

Imagine a present-day reader reaching for Philip K. Dick’s 1964 novel Martian Time-Slip in search of transport, out of the here and now to a psychedelically paranoid near-future Mars. This person might be disconcerted to find two characters discussing traveling to a zone called New Israel—specifically, to a Martian settlement called Camp Ben-Gurion:

As Otto and Steiner walked back to the storage shed, Steiner said, “I personally can’t stand those Israelis, even though I have to deal with them all the time. They’re unnatural, the way they live, in those barracks, and always out trying to plant orchards, oranges or lemons, you know. They have the advantage over everybody else because back Home they lived almost like we live here, with desert and hardly any resources.”

“True,” Otto said. “but you have to hand it to them; they really hustle. They’re not lazy.”

“And not only that,” Steiner said, “they’re hypocrites regarding food. Look at how many cans of nonkosher meat they buy from me. None of them keep the dietary laws.”

“Well, if you don’t approve of them buying smoked oysters from you, don’t sell to them,” Otto said.

Then, a page later:

Steiner felt guilty that he had talked badly about the Israelis. He had done it only as part of his speech designed to dissuade Otto from coming along with him, but nevertheless it was not right; it went contrary to his authentic feelings. Shame, he realized. That was why he had said it; shame because of his defective son at Camp B-G … Without the Israelis, his son would be uncared for. No other facilities for anomalous children existed on Mars …

When Dick became my chosen writer, at age fourteen, in 1978, with Martian Time-Slip, one of my two or three favorites among his novels, the presence of the Israeli settlement on Mars didn’t resound in any particular way. My initial responsiveness to Dick’s work was to delight in his mordant surrealist onslaught against the drab prison of consensual reality—he was punk rock to me. It took me a while to grasp how Dick’s novels, those of the early sixties especially, function as a superb lens for critiquing the collective psychological binds of the postwar embrace of consumer capitalism. Yet to say that he seems to devise his critiques semiconsciously, by intuition, is an understatement. Dick thought he was bashing out pulp entertainment, and he sometimes despised himself for doing it. At other times—and Martian Time-Slip was one of those times—he injected his efforts with the aspiration to raise his output to the condition of literature, employing all the thwarted ambition of a young novelist with nine or ten literary novels (or, as an SF writer would put it, “mainstream” novels) in his trunk, which his agent had been unable to place with New York publishers. Dick had an extrasensory power, however; he was a freaked-out supertaster of repressive and coercive elements lurking inside the seductive and banal surfaces of Cold War U.S. culture and politics. This meant that science fiction opened up his particular capacity for fusing ordinary experience—the emotional and ontological crises of his human characters—to the implications of the hegemonic power of the U.S., which coalesced in the period in which Dick wrote, and which defines our present century. Reality’s surface shimmers open beneath Dick’s gaze. It’s this that led Fredric Jameson to compare him to Shakespeare. This wouldn’t have happened had he stuck to the earnest social realism of his unpublished novels.

Dick’s use of the name New Israel in Martian Time-Slip is pretty stock. Dick traveled beyond North America only once, to a conference in Metz, France, where he delivered a legendary speech titled “If You Find This World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others”—baffling his French fans by opening an early window into the mystical, visionary search that would preoccupy him for the remainder of his life. Then he went home to Orange County, California. His impression of Israel may essentially be derived from Leon Uris’s Exodus, or from some other heroic fifties representation; he principally employs the Israelis in Martian Time-Slip as an anonymous and implacable counterpoint to the abject ineptitude of the U.S. colonists—to highlight the haplessness of their attempts to farm and irrigate the harsh Martian desertscape. As in the excerpt above, the Israelis present a mirror for shame. This matches, of course, a typical midcentury U.S. liberal’s reaction formation, after the discovery of the German and Polish death camps: the Jew as shame trigger, with the survivors idealized for their resilience and strength.

2.

I kept faith with Philip K. Dick through my twenties, even as I expanded my reading in contemporary fiction and, in an autodidactic fashion, began to absorb a certain amount of philosophy, criticism, and theory. The immense reward was to begin to experience Dick as not only a satirist of consumer culture and technocratic optimism—like some kind of more psychedelic version of Mad magazine—but also as a social and political novelist, and an articulate (if sometimes gnomic) diagnostician of the morbid condition of U.S. empire. I had help, of course. The Rosetta stone, for me, was Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Novels of Philip K. Dick, written as his doctoral dissertation in 1982, under the guidance of his advisor, Fredric Jameson. Through Stan’s book I was to some extent absorbing Jameson before I knew I wanted to try. (I call him Stan because he’s a friend; we first met at a bookstore in Berkeley called the Other Change of Hobbit, when I pressed a hardbound copy of the dissertation into his hands to sign.)

Later I turned directly to Jameson, who makes superb use of science fiction generally and Philip K. Dick specifically. The stakes he sets out are the largest stakes possible: “If the historical novel ‘corresponded’ to the emergence of historicity,” he writes in Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, “… science fiction equally corresponds to the waning or the blockage of that historicity, and, particularly in our own time (in the postmodern era), to its crisis and paralysis, its enfeeblement and repression.” I take this to suggest that Dick’s novels, which so often concern themselves with multiple or alternate future realities, are also arguments about nostalgia and trauma. The novels ostensibly concern themselves with the future, but as Dick’s readers know, they often involve attempts to reconstruct or secure some former world that has been wrenched away from the characters in some episode of traumatic rupture: an explosion, an emigration (whether voluntary or forced), a drug-induced spell of hallucination. In Jameson’s fundamentally political interpretation of Dick’s work, these are arguments about which of our multiple alternate or phantasmic “pasts” we must reject, and which we might embrace, before we can achieve a bearable present.

Of course, Philip K. Dick attracts philosophers like flies to sherbet. In my experience, this usually goes well, for both flies and sherbet. A terrific new example can be found in French philosopher David Lapoujade’s Worlds Built to Fall Apart: Versions of Philip K. Dick. Lapoujade’s reading of Philip K. Dick flows mainly through the framework of an older French philosopher, Étienne Souriau, no longer living, whose neglected writings Lapoujade has made it a mission to resurrect. Dick and Souriau seem to have been thought-cousins of a very unusual kind, though it doesn’t seem likely that Souriau would have read him. Lapoujade’s English translator, Erik Beranek, gives a nice introduction to Souriau’s thinking:

Souriau’s philosophy aims to shift the emphasis from a single, preexisting reality … For Souriau, a stone exists, a person exists, and a tree exists, but a forest exists in a manner all its own, separate from the individual trees; likewise, a fictional character like Don Quixote, the idea of a nation, and the unmade film to which an already written screenplay refers all have their distinct modes of existence. Particularly important within Souriau’s analysis of these different modes are virtual existences, which is to say incomplete existences or existences in the making that seem to call for an intensification and development of their own reality … looking at them as existences that make a claim on their own future development. As a result, he is able to push away from the traditional primacy of the already fully constituted to show a picture in which the world remains something in the making.

Beranek goes on to describe how Lapoujade pushes Souriau’s analysis into an explicitly political dimension:

Lapoujade turns his attention to those existences that find themselves dispossessed of their reality; that is, those beings that find themselves to have less reality than others who control what has been determined as most real. If existences need to make a claim on their own reality and right to exist, what happens when an existence is prevented from doing so by other forces within its world and is therefore stripped and dispossessed of the very reality to which it makes its claim?

“Others who control what has been determined as most real.” For anyone newly confronting the extent to which understanding of the history of the Palestinian people has been shaped for the American media, this phrase cannot help but burgeon with implication.

In Lapoujade’s description, the worlds Dick constructs are always on the point of collapsing, precisely because they are worlds whose appearances are determined by a clash of multiple realities—or multiple arguments about the past—vying for control.

As with much science fiction, we find stories of colonization—off-Earth colonization—throughout Dick’s writings. Often, it’s Mars, as in The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Martian Time-Slip, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.” In other novels, like The Crack in Space and The Unteleported Man, the destination is beyond the solar system.

Those stories of colonization that uncover political implications that might matter in thinking about Palestine are, of course, those in which an indigenous population exists before the arrival of Dick’s settler population. The most disturbingly relevant, by far, is Martian Time-Slip. This isn’t because of the presence of the Israeli settlement, though that does feel like a tell—a stray signifier that also functions as a kind of neon arrow directing us to pull off the road and pay attention. It’s because in this novel, the indigenous Martian population—they’re called Bleekmen—aren’t even aliens. They’re nomadic foragers capable of interactions with the settlers on a variety of human-to-human levels: linguistic, professional, and sexual. They are specifically defined as human; they arrived and naturalized to Mars at some unspecified earlier time. However, their marked cultural differences, and their deep acclimation to the conditions of Mars, allow the Earth settlers a margin for apartheid exclusion based on a muddling of the notion of the “alien” and the “human”—or, to be more precise, these qualities allow the settlers to affirm a population’s humanity while systematically violating their human rights.

The critic John Huntington wrote in Rationalizing Genius that “in popular SF, imagining the alien often consists of including or excluding it from the narrator’s sense of what is normal. There is, of course, literature in which beings somehow alien to the author—like Mrs. Moore and Dr. Aziz in A Passage to India—may develop in complex ways because their alienness is not their essence.” Martian Time-Slip conforms precisely to Huntington’s description. It more closely resembles E. M. Forster’s novel than it does a tale of alien encounter, because it isn’t one. In A Passage to India, Mrs. Moore is the white Christian woman whose certainties become cosmically rattled in the Marabar Caves incident, in which a permanently ambiguous series of events gives rise, catastrophically, to an accusation of rape. Mrs. Moore’s subsequent flights of cosmic openness to the implications of her metaphysical revelation, to oneness with the universe, are a contest between Forster’s Orientalism and his critique of the racist paternalism of the British Empire. The analogue to Mrs. Moore in Martian Time-Slip is Jack Bohlen, one of Philip K. Dick’s exemplary Everyman characters. Bohlen makes his living on Mars as a service repairman, tickling dust-choked mechanisms back to life and trying to balance the pressures of bad bosses and a stale marriage (on its “realist” side, Martian Time-Slip is a typical early-sixties novel of infidelity, not so distant from John Updike or Richard Yates) against the fact that the schizophrenic autistic-savant son of one of his neighbors (named as the “anomalous” child who is being cared for in the Israeli settlement) is causing him to hallucinate a nightmare future in which all the Earth settlements have collapsed into bleak, horrifying ruin. The boy in the book, Manfred Steiner, is like the book’s author, a canary in the coal mine, a kind of helpless supertaster of the nightmares to which the colonial project has doomed them all. The boy is also instinctive kin to the indigenous Bleekmen, with whom he shares some kind of collective psychic capacity to live outside conventional Western notions of individual consciousness, and outside of time itself.

Like the Malabar Caves, the visionary nightmares induced in Jack Bohlen by this anomalous child begin to drive him crazy—with insight. What he sees is that the U.S. colonial project on Mars, a kind of interplanetary real estate development scheme with the ominously revealing name AM-WEB (Kim Stanley Robinson translates this as “AM” for American, “WEB” for the snares of capitalism) contains its own death drive. With its prerequisite of denying the full humanity of the Bleekmen, the settlement of Mars is, ultimately, an antihuman project, full stop. Even poor Bohlen, a repairman, a tinkerer, is maintaining the status quo of the settler culture. Even a guy who just wants to mind his own business is inherently complicit.

Lapoujade: “The colonist isn’t just the person who appropriates the land and its inhabitants; she also imposes a new reality on them.”

The Israeli military hero and politician Moshe Dayan: “Jewish villages were built in the place of Arab villages. You do not even know the names of these Arab villages, and I do not blame you because geography books no longer exist, not only do the books not exist, the Arab villages are not there either. Nahalal arose in the place of Ma’alul; Kibbutz Gvat in the place of Jebata; Kibbutz Sarid in the place of Haneifs; and Kefar Yehoshua in the place of Tal al-Shuman. There is not one single place built in this country that did not have a former Arab population.”

Perhaps some among us—those who feel distant enough from the violence to slog through our days without surrendering too many of our cherished myths, without being jarred too much from our attempts to give and receive ordinary comfort to our loved ones, are somewhat like Jack Bohlen. Those of us who abreact and give our energies to protest—the students shattering the calm of our campuses, the no-fun social media friends seeding our streams with confrontational images of the carnage funded by our dollars—are the equivalent of Manfred Steiner, that helplessly visionary child who shrieks in the face of those notions we employ to sustain our complacency.

In the case of Palestine, the first necessity is to grasp the enormous ideological machine that has been necessary to blur the fact of the Nakba. The Palestinian American psychoanalyst and professor Jess Ghannam (on the Ordinary Unhappiness podcast): “We’re talking about seventy-five years of uninterrupted trauma, inherited from generation to generation, from family to family. … [The situation in Palestine] made me rethink the whole concept of trauma. … If you ask an eight-year-old child today in Gaza, ‘Where are you from, where is your family from?’ they never tell you the city that they’re currently living in—they will tell you the city that their great-grandparent was dislocated from in 1948.”

I learned the word Kristallnacht before I can remember. I was in my fifties when I first heard the word Nakba. Ideally, one goes on learning.

3.

I want to inoculate my interpretation of Martian Time-Slip against the protest that Philip K. Dick himself, had he lived long enough to learn of it, would reject it out of hand. In fact, there’s almost no question he’d have done so. Dick inherited a grain of antiacademic suspicion from the outcast milieu of SF writers that gave him his professional home and provided him with the consolation of friendships with other formidable intellects, from Robert Heinlein to Ursula K. LeGuin. He was, at times, bewilderingly wrong in allowing his own intuitions to lead him to disastrous conclusions, causing him to feud about feminism with Joanna Russ and to accuse Stanisław Lem of being an agent for the KGB. There’s a great chance that Dick, steeped in his obsession with the historic evils of the Third Reich, might never have modulated that heroic picture of the founding of Israel.

Though one is, ideally, always learning. So, who knows?

In my 1998 novel Girl in Landscape, I attempted to triangulate Martian Time-Slip with two other influences: the Westerns of John Ford, particularly The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and Forster’s A Passage to India. It wasn’t that I thought I could improve on Dick’s novel, but there was something I wanted to explore in shifting his Martian frontier a few degrees closer to Ford’s settlers on the frontier, and to the British Raj. (An Anglophile reader as a kid, I’d soaked up a lot of colonial narratives: Greene, Maugham, Orwell, et cetera.) My conscious decision was to hook these materials to the archetypal science fiction vision of a frontier Mars—not only Dick’s but Ray Bradbury’s too.

So, my off-Earth colonists landed on the desert planet. Their settlement is a tenuous and fragile proposition set amid the dusty ruins of an indigenous culture which—like Ford’s Native Americans, and Forster’s Indians—remains present yet is somehow totally defined by the settlers as residual, a living relic of the past. I called them the Archbuilders.

When the book was few years old, I got a call from my agent. The French director Leos Carax was interested in making a film from the book. I’d seen two of his films and was in awe of his artistry. Carax would be in New York soon, and hoped to meet to discuss his proposition. I was given a date and time to find him for coffee at the Ace Hotel.

Here’s how I’ve always told this story previously: the morning of my meeting with Carax was a comedy of errors. Which it was, truly. I mistakenly arrived an hour early. There was a chance I’d spoiled it all right there. Carax wasn’t ready. I waited in the lobby and he emerged, grudgingly, perhaps a bit jet-lagged—in any case, not in the right mood. Yet we tried. We sat over coffee. I mistakenly thought Carax wanted me to write the film for him, which I had already told myself I didn’t want to do—or, rather, had thought I shouldn’t want to do—and before I realized I might, I’d already declared I didn’t, and annoyed him.

Here’s the part of the story I caused myself to remember by writing this: I believe now that there was another way I disappointed Leos Carax, besides obnoxiously announcing I wouldn’t write the screenplay. Carax told me he wanted to rework my story about Mars to make explicit reference to the Palestinian territory. I’ve always believed films are different from novels, and that filmmakers should feel free to transform the materials they adapt—in fact, this is one of the reasons I’d determined I shouldn’t be the screenwriter, in order that Carax not feel bound to the particulars of my novel. He should do with it whatever he wished.

Nevertheless, in mentioning Palestine, Carax surprised me. And my surprise was visible to him. And, I think, a disappointment to him.

I told him it was a great idea. Still, he’d seen my confusion. Though I’d wished to pursue the anticolonial thread running through John Ford, E. M. Forster, and Philip K. Dick, and though I’d set my fever dream in a desert landscape, I hadn’t followed my own implications to the contemporary framework that Carax felt I must obviously have had in mind. I’d only accidentally written about Palestine. For Carax, I suspect, that was unfortunate.

4.

It took me a long time to see that if Philip K. Dick was authentically of use as a political philosopher, this would be because one could discern, within his bleak diagnosis of the traumatic collapse of stable reality and the dire prospect of maintaining steady contact with the human in a world of corporate simulacra, within his fundamental (and for me, for so long, attractive and necessary) dystopianism, a grain of utopian desire. A grain of utopian belief, of utopian imperative, even. In fact, the utopian desire in Dick’s novels had been sustaining me all along, without my understanding it well enough to name it—until I came across Lapoujade and Souriau.

You may find, as I do, that you need to read Souriau quite slowly—you may also agree with me that the reward for doing so is considerable. Here is a paragraph, as translated by Beranek and Tim Howles:

It is certainly of great consequence for every one of us that we should know whether the beings we posit or suppose, that we dream up or desire, exist with the existence of dream or of reality, and of which reality; which kind of existence is prepared to receive them, such that, if present, it will maintain them, or if absent, annihilate them; or if, in wrongly considering only a single kind, vast riches of existential possibilities are left uncultivated by our thoughts and unclaimed by our lives.

Lapoujade, in more accessible language, routes such insights through Philip K. Dick, writing that, in Dick’s novels, “the world must be continuously produced.” Elsewhere, Lapoujade remarks: “Empathy is what allows one to circulate between worlds.” Here, then, may be one definition of the ineffable process Souriau calls instauration: the conscious and continuous affirmation of the plurality of existences other than our own.

To return to Jess Ghannam (again on the Ordinary Unhappiness podcast): “One of the ways in which psychoanalytic theory is so deeply powerful is that, when it’s done well, instead of being attached to a single, unconscious fantasy as the only way to have desire realized, you have opportunities to have multiple kinds of fantasies, so that … you have a more complex repertoire of opportunities to have desires realized. … Something really phenomenal will happen—not just for the psychoanalytic community for the world community, if you begin to see Palestinians and Palestinian children as human beings, as legitimate and entitled to the same kind of rights as any other human being, and entitled to the ability and the capacity to thrive and play. That’s going to help us get out of this mess. … We have to make psychic space for thinking about things in a much richer, complex, nuanced way, and if we don’t do that, we’re headed for something really horrific.”

What is Dick’s vision of utopia? What vision is possible in such a world as he and Souriau describe, this world of absolute instability among rival realities? In effect, the question contains the answer: in Dick’s novels, again and again, the veil of a unitary reality is ripped off, in favor of the revelation that we live in an existential abyss—one that is also an existential plurality. However painful the transition may feel, the true nightmare isn’t this abyss of infinite possibility but the attempted imposition upon it of a single viewpoint. Dick’s books are full of tyrannical characters, possessing nightmare capacities to infiltrate all minds to produce fascistically unified worlds. We have no choice but to overthrow them.

This essay derives its essence, though not its present form, from a talk given at the Philip K. Dick Festival in Fort Morgan, Colorado, on June 15, 2024.

Jonathan Lethem is the author of Brooklyn Crime Novel and twelve other novels. He teaches at Pomona College and lives in Los Angeles and Maine.