Detail from Rogier van der Weyden, Annunciation Triptych, c. 1440. Public domain.

In the Rogier van der Weyden, Mary is reading about her future life in the Bible.

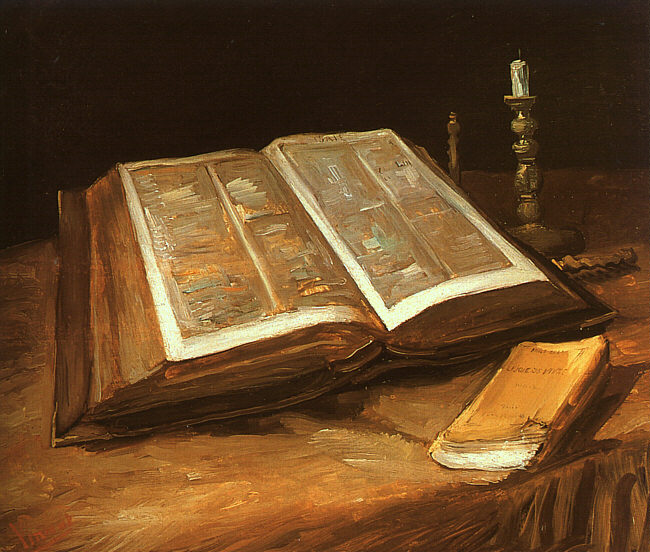

Van Gogh paints the Bible as a still life.

Vincent van Gogh, Still life with Bible, 1885. Public domain.

Goya paints his model posing but still dressed.

Both of the last two are an invitation.

Both lie open on drapery.

Francisco Goya, La maja vestida (The Clothed Maya), 1801–1803. Public domain.

And how similar in their spatial perspectives are their open invitations.

Love, John

Chaïm Soutine, Le bœuf écorché (Carcass of Beef) (1925). Public domain.

There is this saying: “I can read them like an open book.” Isn’t it a very nice way to express this desire we have to access what’s inside? Inside what we are facing and its mystery. How we wish to penetrate the outside world surrounding us, not to take control of it but to feel more completely a part of it. To overcome the isolation we feel in our flesh. The terrible boundaries of the body … See how Chaïm Soutine was obsessed with reading the inside! Le bœuf écorché offers itself like an open book too …

Love, Yves

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Pierrot (also called Gilles), 1718-19. Public domain.

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Le Savoyard et la marmotte (Sayovard with a Marmot), 1716. Public domain.

“To overcome the isolation we feel in our flesh. The terrible boundaries of the body …” Your words and the Soutine unexpectedly made me think of Watteau and his players and clowns. All the dressing-up and frivolities to hide the terrible border. I was looking for Gilles, and I came across the Marmot. One of our Alpine marmots that stand on two legs to see across the snow, now a gag in a box to make people in the cities laugh. Then I found Gilles and the donkey below and behind him. (Donkey and marmot might have a lot to talk about.) Inside his costume, Gilles’s body has no border because joke after joke has dissolved the body into a sky. His body is becoming a cloud. He is painted like a landscape.

Love, John

Max Beckmann, Carnival Mask, Green, Violet, and Pink (Columbine), 1950. Public domain.

Gilles says: ‘‘I’m a stranger in a stranger world. I’m here but belong nowhere. I drift in this life of exile.” The Savoyard with his marmot, from Saint Petersburg, replies: “Cheer up, don’t fuss! See the sky today? No drama can happen under this blue. Nothing to worry about; the light won’t fade, even when we die.”

Over a century later, in New York, Max Beckmann paints a woman wearing a carnival mask. A cigarette in one hand, a clown hat in the other. She says nothing, but her black mask doesn’t hide what her eyes tell: “Darling, you are as bad as me. Who do you think we are?”

Beckmann was a man of faith. “The great emptiness and enigma of space,” he named God. All his life, he was trying to enlarge and deepen his knowledge of the world we live in. Light, as it were, was the vehicle for his quest. Drawing, the road. Hence his use of black.

Colors in his paintings come after form. They bring complexity and unexpectedness.

Look at a black-and-white reproduction: nothing essential is missing. Probably the same is true of Georges Rouault (who was born thirteen years before Beckmann and died seven years after). He too painted actors, clowns and mythological scenes. He too had a strong faith. To the point that he could paint a sun circled with black.

Love, Yves

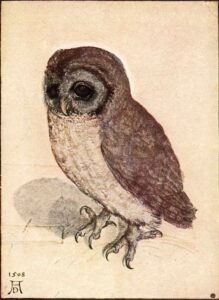

Albrecht Dürer, Kleine Eule (The Little Owl), 1506. Public domain.

A few days before I got your Beckmann, I received a postcard from Arturo. Here it is. I put Dürer’s Owl beside Beckmann’s Columbine, and together they made me smile. Their two faces and tummies wink at each other.

Also, both paintings present a species.

He is all screech owls throughout time; she is all women wearing a carnival mask! And of course this is linked with what you say about outlines, drawing and the use of black. And this made me think of images that insinuate the opposite. Kokoschka was an exact contemporary of Beckmann’s. In Kokoschka, nothing is permanent and all is transient.

Even in his self-portrait with his beloved Olda, which is intended as a testimony to their lasting love, every brushstroke is fugitive, fleeting, momentary. And these qualities are proof that they are alive.

Kokoschka is very different from the Impressionists, for whom shifting sunlight was a miracle and a promise. For Kokoschka, light is a parting touch. When he was painting an aerial view of the Thames in London, I accompanied him for a moment to the roof from which he was painting it. This was in 1959. And his gaze was like that of a migrant bird about to leave.

Love, John

Helene Schjerfbeck, Self-Portrait, 1945. Public domain.

The gaze “of a migrant bird about to leave.” Yes, a gaze that embraces space in such a way that the distant and the near are brought together. And this gaze creates a kind of map on which miles or kilometers pass by like the hours of a day.

Facing this, Kokoschka feels how fugitive light (and life) is!

Zhu Da, who belongs to an ancient Chinese tradition, feels the same but believes that light and life are eternal and that he is the fugitive! It’s a question of perception.

Remember when, as a kid, I stood with you in a phone booth on a bridge in Geneva? And watching the water flow beneath our feet, I got scared and cried, convinced that we were drifting away.

Zhu Da also drew and painted several species of plants, birds, and fishes. (Maybe he even drew a mouse, which Dürer’s owl would surely have gobbled up a century and a half later!)

But to Zhu Da, unlike Dürer, the idea of a self-portrait would never have occurred in the same way because the “self” already belonged to the species and the landscape and could not be separated from the rest of the creation. We couldn’t be further away from the mindset of modern and postmodern Western culture.

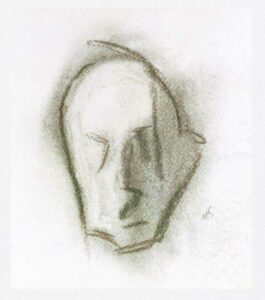

Hence Giacometti’s and Schjerfbeck’s self-portraits. Following Kokoschka, they feel it’s “departure time.” Toward his future life for Alberto, to her approaching death for Helene. And both look back …

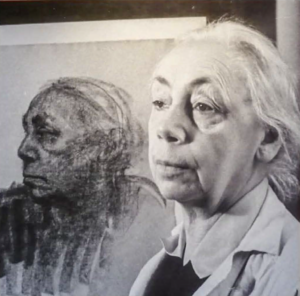

For your pleasure, I add a photo of our beloved Käthe Kollwitz next to one of her self-portraits.

With love, X, Yves

Käthe Kollwitz. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

One of the first old master paintings to enthrall me and seize my imagination was Poussin’s Et in Arcadia Ego. The three shepherds come upon a tombstone and thus discover that even in carefree sublime Arcadia, death occurs.

Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia Ego (deuxième version), 1628. Public domain.

Poussin was obsessed with the question of what was and what was not eternal. Let’s look at his Landscape with Saint John on Patmos. John is writing his vision of the Creation and God in a landscape that spans the whole of Time. And I want to compare this with a landscape by Zhu Da.

Nicolas Poussin, Landscape with Saint John on Patmos, 1640. Public Domain.

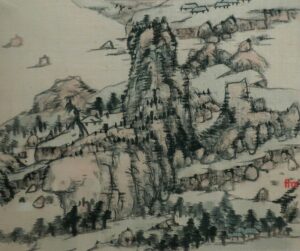

Zhu Da (Bada Shanren). Public domain.

In the Poussin, the trees, the rocks, the distant mountain are painted in such a way as to emphasize their density, solidity and permanence. And in the Zhu Da, by contrast, the trees and rocks and mountains are brushstrokes and gestures. His vision is calligraphic.

At the same time, both landscapes are full of a sense of space, distance, nearness, and permanence. Both question the notion of eternity. But what creation means to each of them is very different. For Zhu Da, God has written the world and he transcribes it; for Poussin, God has molded the world and he measures it.

For Zhu Da, there are no horizons but only pages and the spaces between words that are wisdom. For Poussin, there is an encompassing emptiness that has to be filled with prayers and angels.

In their later work, Giacometti will become, within the European tradition, a kind of calligrapher. And Helene Schjerfbeck a kind of keener.

Love, John

From Over to You: Letters Between a Father and Son, forthcoming from Pantheon Books in November.