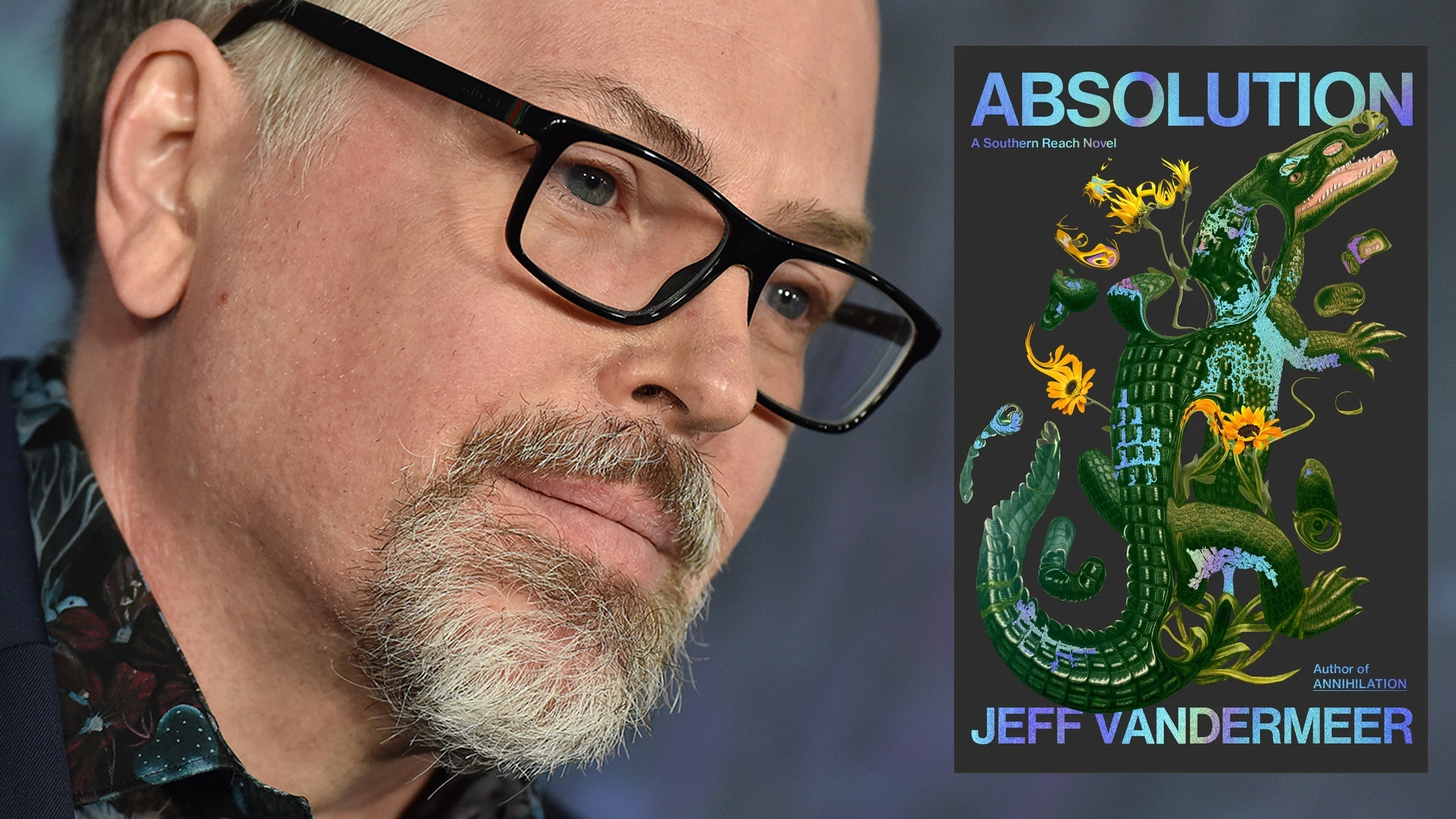

Ten years ago, author Jeff VanderMeer released three haunting novels delving into the mysteries of Area X, an abandoned coastal region transformed by forces beyond human comprehension. The publication of Annihilation, Authority, and Acceptance (collectively referred to as the Southern Reach Trilogy) earned him instant stardom within the science-fiction community for their explorations of environmental collapse, governmental dysfunction, and horror. Annihilation won both the 2014 Nebula and Shirley Jackson Awards for Best Novel and was adapted into Annihilation (2018), a film by director Alex Garland, starring Natalie Portman.

VanderMeer has been busy ever since, publishing multiple novels and essays often centered on similar themes while vocally advocating for climate change solutions and conservation efforts from his home in Tallahassee, Florida. A decade has passed since readers were introduced to the Southern Reach Trilogy, but its sci-fi plotlines of mutating landscapes and oppressive, unhinged government bureaucracies often feel more real than ever. If anything, it’s the perfect time for VanderMeer’s return to Area X with his new novel, Absolution.

Published on October 22nd, Absolution serves as both a prequel and sequel to the first three books, and features the return of two characters from the original storyline. Popular Science spoke with VanderMeer just two days after Hurricane Milton’s devastating Florida landfall in Florida. The prolific author and literary critic discussed his new novel’s eerie, intentional similarities to reality, the importance of both fiction and humor in dark times and Elon Musk’s slow transmogrification into a “deranged court jester.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The original Southern Reach trilogy came out in 2014. How have the themes of climate change, technological misuse, and corrupt bureaucracies evolved since then?

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that there’s actually a hurricane in Absolution… [A hurricane] is almost something that’s too big to imagine, especially when you’re overtaken by it. We’re building in places we shouldn’t and destroying the surrounding environment when there are these natural buffers that would actually help protect against storm damage and flooding. There’s also an exploration in Absolution of extremely dysfunctional systems and how they wind up deranging and deforming people who have to work under them or within them.

The things in the book are not that far off from the derangements these systems impose on us right now. They may seem more banal, right? But they’re actually just as devastating.

It also feels like even many Silicon Valley’s tech leaders are rapidly transforming into more twisted versions of themselves, much like what happens to characters after entering Area X.

Something I like to do in my writing is take the persona of someone that has to do with bleeding tech, [someone] involved with it that sometimes winds up deranging or derailing the tech. For example, you have Elon Musk establishing his SpaceX spaceport right next to a wildlife refuge and not caring if he destroys a migratory bird pathway. [He has] no understanding of the world around him whatsoever…

[Related: SpaceX accused of dumping polluted Starship wastewater in Texas for years.]

Is there a way out of that mindset for people like Musk and his fans?

I don’t know. I was really quite shaken—even though I shouldn’t have been—by those images of Elon Musk looking up at Trump. The look on his face like a deranged court jester in Titus Andronicus or something, you know? Like something from The Masque with a Red Death. We’re seeing someone who’s supposedly connected to the quote-unquote “logic of technology” debasing himself in such an illogical, almost superstitious manner. Almost medieval. It was quite shocking.

Speaking of ‘medieval,’ how do people break out of that ‘superstitious’ worldview regarding tech culture’s inherent, unquestionably positive benefits?

It’s like when a person grows up in a fundamentalist religious family, shakes that off, becomes progressive, but does not shake that underlying mindset. They apply the same kinds of things to the new ideology. The same thing applies to what we’re talking about here.

Even solar energy is being turned into an extractive industry. In Massachusetts, they’re choosing sites not based necessarily on suitability, but on the fact that they can also harvest the site for timber and do sand mining before they install the panels. You can begin to lose hope in the logic of these things under capitalism, because if even solar can be turned into something that’s actually a negative for no good reason except for greed, then we really haven’t learned the lesson.

[Related: Solar power got cheap. So why aren’t we using it more?]

What is the solution in those situations?

We should have sustainability hardwired into our ideas about new tech. It’s kind of alarming when we get innovators who don’t think about those issues. It feels a little bit like there’s this kind of “brash, swaggering tech bro” ambivalence of, like, “We just need to disrupt this field. We don’t need to really worry about all the consequences.”

Florida is a microcosm of how it’s playing out across the US. Some states are in line with certain federal practices, and then some states are doing a bunch of incoherent, illogical things. And so ultimately they wind up just treading water.

Also, this idea that we can somehow limitlessly pull stuff out of the real world to support the virtual world without the virtual world eventually collapsing—again, it’s kind of deranged. It comes back to this con job that a certain section of those cliche tech bro have sold the public on how ‘innovation’ is any kind of new thing that’s bright and shiny and has enough of a will to power behind it. That’s really what it is. They’re willing something that’s bullshit into power. It’s literally the definition of a con job.

[Related: Florida is a preview of our climate change future.]

You previously wrote about a writer’s imperative to incorporate climate change and irresponsible technology in their work. Are you seeing that happen more frequently?

There’s a lot more of it in fiction, and in the right way. I don’t really think fiction should be predictive in the sense of being something we refer to for actual policy. I think it’s more useful to give us psychological profiles and an interiority such that certain effects of the climate crisis kind of live in our bodies.

It’s really quite important to think of climate change not as a science fictional element or device, but something we’re actually going through right now. It’s not the province of the near future. It’s right now. Just because it’s unevenly distributed, it doesn’t mean that it’s not happening in pretty intense ways, even if it’s not happening that way to all of us.

How can writing from an non-anthropomorphic viewpoint actually help humanize and contextualize stories, especially regarding climate change?

One thing fiction can do is bring us to a greater understanding of the non-human world, and that can have an impact in how we view the value of it. Because it’s so important to our own survival, too—beyond the intrinsic ethics of just not destroying and killing things arbitrarily for no particular reason. You try to get somewhere that the reader will follow you enough so that they can still kind of understand it. They can kind of inhabit a different point of view.

[Related: Why the tech billionaires can’t save themselves.]

What keeps you going these days? What keeps you hopeful for the future?

I can speak more toward Florida right now than anywhere else. At least here, state leaders have overstepped their bounds so much on some of these policies to the point where you see a lot of local activism. You see people on a wide political spectrum banding together to vote out county commissioners and others. You’re seeing more involvement in local government from young people and just from people in general. You’re seeing more coalition building along very unlikely lines, because of common interest, because you’re really talking about people’s survival to some degree.

It can’t be all gloom and doom, right?

As a novelist, I’m never really that interested in something that’s monotone, so Absolution is probably the least about environmental issues and most about, like, dysfunctional systems. But there’s a lot of absurdity and humor to be found in that, so it’s actually a fairly funny book, despite also being very serious. I think that’s important, too.

Humor is a really powerful way of exposing some of [those issues]… I think it’s a very effective way to keep extremists off balance.