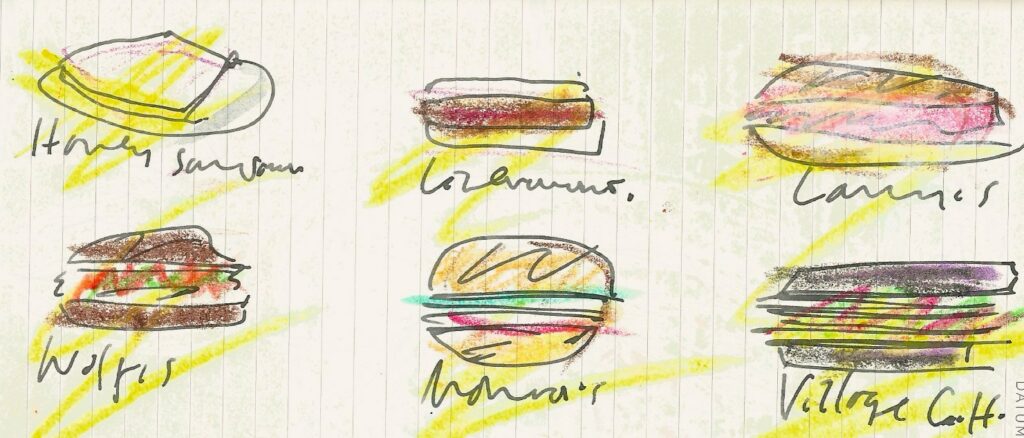

A history of sandwiches. Drawing by Todd McEwen.

It was California, so, sandwiches. I sat by the window overlooking Balfour Avenue, at our kitchen table. Its plastic cloth, gray, with a fringe of white yarn. (How did she ever wash that thing?) My mother was moving between the sink and the stove, framed in the doorway to the dining room. Outside was a big lantana with orange moths in it. I remember this as the time when we started to talk to each other a lot. Was I four? I said to her that I was glad I didn’t have to go to school yet. “Oh, yeah?” she said.

The sandwich dear to me in those days was Monterey Jack with mayonnaise and lettuce on Van de Kamp’s sliced white bread.

MY WHOLE LIFE HAS BEEN MAYONNAISE

There was a perverse ancillary reason that I liked this sandwich: an ancient cartoon that returned again and again, on Sheriff John’s Lunch Brigade on KTTV, which I never missed. In this, one of the hundreds and thousands of characters from the early days of commercial animation—Sparky? Inky? Horny? Drecky?—ate a sandwich that looked like mine and smacked his lips loudly while he did it. Of course, I could only smack my sandwich this way when I was in front of the TV and my mother was out of the room, and out of earshot. But it did make it taste better.

A grilled cheese sandwich, made on our aluminum griddle with the rounded corners. Same bread, same cheese. Maybe Tillamook cheddar once in a while. Perfect. Golden. A big hand for my mom, folks.

Honey sandwiches. Van de Kamp’s white bread, butter, and Sue Bee whipped honey. I still have a horror of honey you squeeze out of a bear.

I liked peanut butter and jelly. Everyone does. But while Welch’s grape jelly was the national standard, I accidentally discovered that I also liked peanut butter and Rose’s lime marmalade, something my parents had around from a trip to Canada. What a little snob! But you should try it.

I liked baloney OK, but I really liked liverwurst. My father was particular to call it braunschweiger. Oscar Meyer, or, better, Farmer John. My dad would add raw onion. A step too far for me at that time. But when I later encountered the liverwurst sandwiches at McSorley’s, packed with onion and mustard that blows your head off, I found that I was, in fact, prepared.

***

Later in life I developed a real taste for Bermuda onion sandwiches. Just onion. Out of simple human compassion, I try to eat these when no one else is home. One day however I had just polished off an entire purple beautiful onion on pumpernickel when the phone rang. It was the dentist—where was I? I’d gotten the day wrong, something that often happened when I was using diaries from Ordning and Reda, who print them in such an ultra-cool light gray that you can’t see what fucking day it is. “But I’ve just eaten an onion sandwich,” I said. “Oh, that’s OK—come on over. Come on now.” I brushed my teeth three times, which ruined the heady experience of the sandwich, and ran over there. I opened my mouth and they were truly amazed at how I could fill up their entire practice, really the whole building, with this essence of one onion. They’re still talking about it.

I was once alone in winter in a house on Long Island. The salient features of this house were a big dining table at which I could work, a faulty wood stove that almost killed me one evening, and a closet full of the owner’s Ballantine’s scotch and Pall Malls (I more or less replaced them as I used them). There were also a lot of books by Simenon and Bemelmans. What I brought to this solitary party were onions, cheese, ham, and beer, from a little shop I could cycle to on the ice (this was pretty Buster Keaton sometimes).

There was a week or so in deep winter when it was so frozen that I had to stay indoors. There were cardinals on the fence. After I finished working for the day I would select a handful of Simenons, pour a glass of beer, and sit at the luxuriously large table and read in the heat of the stove. Each time Maigret ordered a glass of beer from the bar in the Place Dauphine and drank it in front of his stove, I drank one too. If he ordered a sandwich, I had a sandwich. When he smoked his pipe, I smoked mine.

Was this any way to pass the coldest part of the winter? Yes. It was. I kept myself alive, kept the villagers at a distance. After all, I was “trying to work,” the phrase that I’ve used against everyone I’ve ever known. I have to.

Sometimes it got a little nuts because there was a radio station in Bridgeport that played the most adorable R&B records on Saturday night and I’d bop around the living room and then zoom back to the big table for another sandwich and a glass of beer and then drowse, until the whapping of the mousetraps in the kitchen awakened me—there was nothing to eat in there but the detritus of my sandwich-making and a big bar of Ivory soap. They would run across the floor to get at it.

***

An autumn lunch in Edinburgh. Drawing by Todd McEwen.

My dad had a laboratory accident in high school where his hair caught fire and the inside of his nose was scorched. After that he couldn’t taste or smell much (his hair survived). His gustatory life was muted from that period. He liked strong tastes, though now that he’s ninety he only likes candy. Where he got a taste for German and Jewish stuff I don’t know—he grew up French Catholic, eating baked beans and pancakes in the middle of nowhere, and in the Navy he was stationed in Nassau. Once in a while he’d take me to LINDEL’S, on Lincoln Avenue in Anaheim. There I’d watch him eat gefilte fish and pastrami and sauerkraut. This place was owned by a rotund, jovial man who always came over to our table. My father seemed really grateful to this man for selling food that had flavor in Orange County, California, in 1958. One day my dad asked him if he was Mr. Lindel? (Pronouncing it like “kindle.”) The man said, “In a manner of speaking, sir. The name of my restaurant means ‘Lincoln Delicatessen.’ ”

(My parents are, in actual fact, the last people in the world who eat baloney. After a twenty-four-hour airplane trip it’s a real treat to be offered one of their quite dry one-slice baloney sandwiches and to be told “We forgot to buy beer.”)

***

In 1964, we moved to a more genteel, more sophisticated town. I’m not proud of it and I don’t like mentioning it. It was Palo Alto, California. New place, new sandwiches. The real discovery was the VILLAGE CHEESE HOUSE, a large deli with elegant stuff—my grandmother used to send me chocolates from there that had baby ants, bees, and caterpillars in them. They were dead. Crunchy.

This shop was run by Europeans. Their preferred breads were pumpernickel and rye, and they put heaps of meat and cheese onto their sandwiches, along with mayonnaise, mustard, and PICKLES, which I had never agreed to and I thought I’d probably hate, but I didn’t and now I MUST have them.

My mother spent most of her life in the frozen food section of the supermarket. There she found “Larry’s” frozen poor-boy sandwiches. These came wrapped in silver mylar and you put them in the oven for half an hour. They fascinated me because they had mayonnaise in them along with ham and baloney (I guess) but the mayo became nice, not horrid, even though it was hot and had once been frozen. Mayo, mayo, mayo. I coveted these but only got one every couple of months.

***

A HAMBURGER USED TO BE CALLED A HAMBURGER SANDWICH

When my father had to go out of town, our mother would take us to MOORE’S BURGER HUT, which sat practically right on the railroad tracks. It was built of cinder blocks and it was very smoky inside and the hamburgers were great. N.B.: the construction of MOORE’S BURGER HUT was identical to that of KIRK’s, in Los Altos—was there a guy driving around California building the exact same burger joint everywhere? Beige cinder block, linoleum, beams, the grill half indoors and half outdoors?

HIPPO, Menlo Park. Funny murals, big fat hippopotamuses waddling around and enjoying hamburgers. No one needs funny murals if you have good burgers. My father always threatened to order a Cannibal Burger, which was steak tartare, but he never did. He just liked hearing us squeal.

Hamburgers, the smell of bad ones, pervaded Third Street in San Francisco. Walking from Third and Townsend up to Market Street was like crawling commando-style through a vat of frying onions. You still smelled like it the next day. My mother hated this.

In North Beach there were all these family Italian places along Columbus Avenue and they sold giant hamburgers on San Francisco sourdough, stuffed with onions and sautéed green peppers and garlic.

***

Various pleasures of sandwiches. Drawing by Todd McEwen.

New York City. Now that is a sandwich town. WOLF’S. ZABAR’S. CARNEGIE DELI. THE STAGE DELI. KATZ’S. B&H. BARNEY GREENGRASS. MURRAY’S? Forget it. I’m not even going to talk about bagels. It’s just too huge.

In my neighborhood there was TA-KOME FOODS—“Home of the Hero.” Far from it, I’d say. The rolls were not nice and the place smelled. It could have been cat piss or mouse piss or roach spray. Or all three. Bigger men than I swore by their meatball heros. (I’ve never eaten a meatball hero, and hope I never have to.) I preferred ROUND sandwiches to LONG sandwiches. A WUSS.

There was something kind of urine-y about all their sandwiches, come to think of it. They did that thing of sprinkling every sandwich with oil and vinegar, whether you wanted it or not. Everything at TA-KOME was slightly obscured, like it was an aquarium, because of the steam tables and because they never really wiped the splash guards. Or anything, really.

MAMA JOY’S was cleaner and tastier, and more expensive. The cheeses were much better. The main experience was the enormous guy with the enormous mole on his face, the Ham-and-Salad-Tub Man.

The bread and rolls were better here—I don’t think TA-KOME had real rye at all and they certainly didn’t have pumpernickel. At Mama’s the lettuce and tomatoes were fresher. We could buy Bering cigars, our pipe tobacco (Sobranie and Mac Baren), and stuff like that. We experimented with Tijuana Smalls. IDIOTS.

I went through a period when I ordered everything on whole wheat. But that gets tiring, no?

One day Isidor and I decided to invite our professor to lunch. He was very late and we finally phoned his office—he’d probably been hoping that we’d forgotten about it. Anyway he finally came down the street and he seemed pretty unimpressed by the grilled cheese sandwiches I made (just like Mom’s) and the Campbell’s tomato soup, I mean he was about as impressed as he was with us as scholars.

Isidor was not a sandwich type of guy. So whenever I went over to his and Mary-Ann’s place on the east side, I would stop at this deli on his corner and pick up a baloney and Swiss on a roll. Just to annoy him.

***

I surprised myself by getting a 1000% Celtic Girlfriend. She was Scottish and Irish AND Welsh!

Her pop was a guy who used ham sandwiches as a way to avoid his family. He was on a totally different schedule from the rest of them, on a different plane entirely—even though he made it appear that he lived among them. He always had soup for breakfast, and six days a week he took a very early train into the city. He left his office on Third Avenue just as rush hour was ending and arrived at home about seven thirty, when most commuters had already had dinner. As his wife prepared their meal, he had three big scotches. Then he ate a little bit, asked a few polite questions about how everybody was, and went to bed.

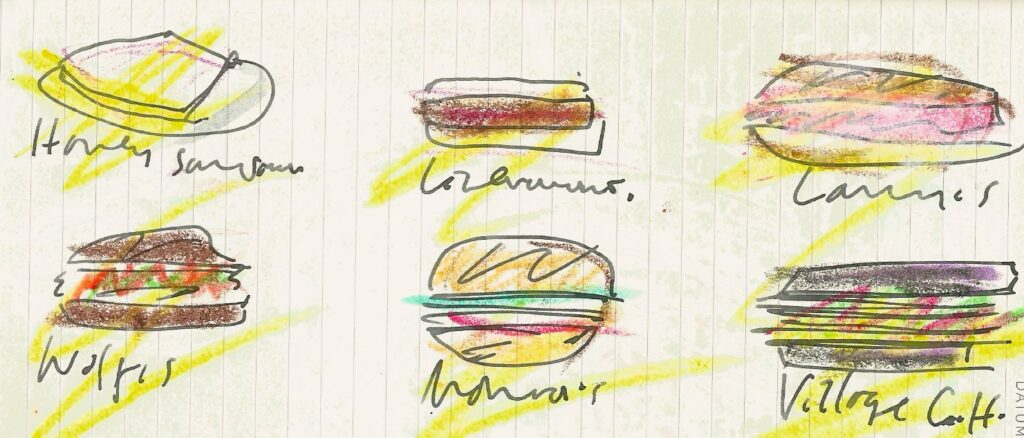

Sunday was the one day he was literally, inescapably at home, and he struggled with that. When things got too familial, too American, who knows, too CELTIC, he retreated to the kitchen. Dads always retreat. They can’t bear to see what they’ve wrought. He had these stoneware beer steins in the refrigerator that said Löwenbräu on them. He’d fill one up with a can of beer and eat a ham sandwich. The ham sandwiches were made by his wife, and they appeared always to be in the fridge, waiting. Enviable arrangement. Day or night, he stood at the kitchen sink, looking out at the backyard. Like a Hammershøi painting of a scene from Updike.

This kind of thing really works as a break for MALES, but MALES don’t really need, or deserve, a break.

***

There is nothing to be said about Boston, except that they had excellent tobacco and there were two sandwiches, both in Cambridge. One was MR. BARTLEY’S, where the hamburgers are very like KIRK’S. The other was a totally fake but quite magical German restaurant, the WURSTHAUS, where the sandwiches were generous and tasted like those at the VILLAGE CHEESE HOUSE. Maybe it was the pumpernickel or maybe I was just missing my family.

Durgin-Park didn’t have sandwiches, and even if they did, you’d have had to get some big guys to help you shove a ton of prime rib to the other side of the room even to find them. Jacob Wirth’s had sandwiches, and good ones—corned beef, tongue, Westphalian ham, even sardines—but I only ever had hot bratwurst with beans and sauerkraut.

***

Breakfast. Drawing by Todd McEwen.

The tramezzini of Rome. There is something slightly strange about them. They’re surrounded by a kind of oily glow; they look like they’d come apart in your hand. I’ve never seen anyone eat one, either, yet there are always piles of them. There is a certain sense to this: it’s ROME. What do you need a sandwich for?

They say you can’t get a bad meal in Paris. This is a stupid and pathetic thing to say, because I’ll tell you exactly where you can get one: at a blue-colored café on the rue de l’Odeon. They have the most awful, inept, disgusting salmon sandwiches ever made. Write me and I’ll give you the address.

Isidor and I were wandering around London. We passed a pub where there was a sign announcing

FRESHLY CUT SANDWICHES

This incensed Isidor, who stood looking at this sign in fascination, saying, “Do you get this? This implies there’s some kind of art, or technique, to merely …”

On Calle del Laurel, in Logroño, Rioja, the street of vendors of tapas and pintxos, roasted calamari, pulpo, tuna, cigalas, patatas riojanas, olives, meatballs, mushrooms, manchego, idiazabal, bacalao, anchovies, morcilla, chorizos, croquetas, torreznos, patatas bravas, tortillas and padron peppers, they don’t need no steenking sandwiches.

***

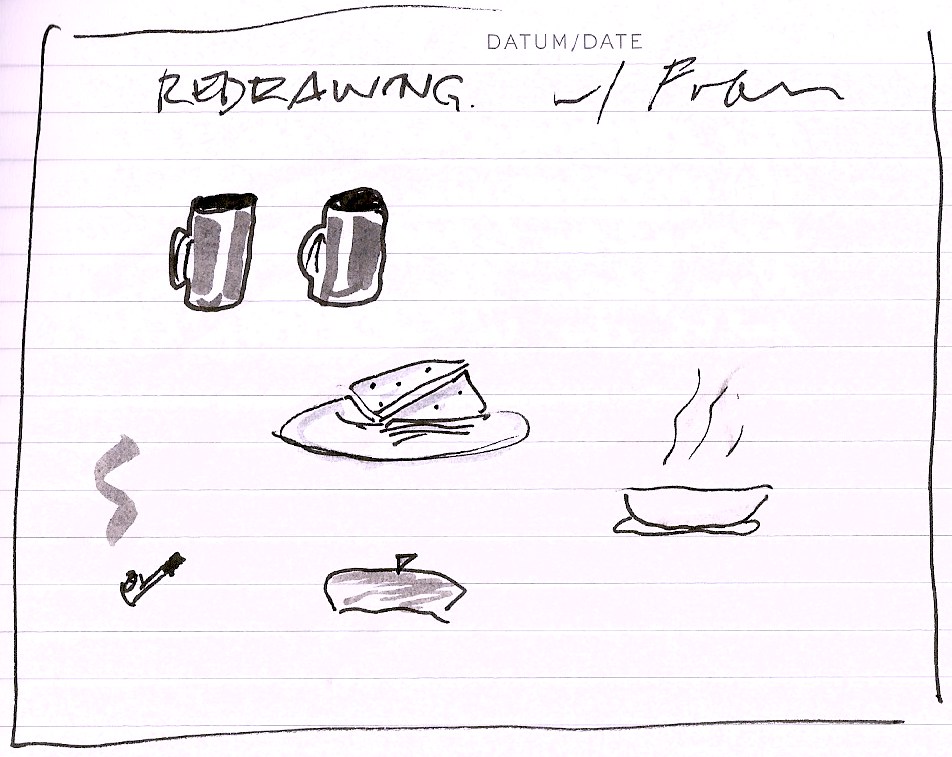

Sandwich dimensions. Drawing by Todd McEwen.

What is called the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland should not be, because there’s nothing united about it. There are cucumber sandwiches, but bleccch. There were the historic duck-paste sandwiches that killed a lot of people in Scotland. Bleccch. There are chains that try to imitate American delis, but bleccch.

What the English call a ham sandwich contains only the faintest memory of ham.

I had to resort to working at an English university, out of poverty. Of imagination. And money. This was a dire wholesale reentry into the domain of the sandwich. At the university there was nothing to eat BUT sandwiches. They appeared at any and every meeting, seminar, class, WHATEVER, from a secret location, and they were always damp. The cheap, sweet mayonnaise (don’t ever visit England) made me nauseous and the margarine gave me diarrhoea (that’s how they spell it!). The fillings tasted like they were scooped up off the floor.

Just when I’d finished one sandwich, the one I couldn’t imagine how I was going to swallow, I’d have to go to a MEETING, where there would be PLATTERS of sandwiches, the same silly, terrible ones I’d just paid money to GAG DOWN because I was working a ninety-hour week and had no time to go anywhere for decent food. Not that there was any. It was ENGLAND.

They RAMMED these platters and platters of sandwiches at me, and down me, until I had to QUIT.

***

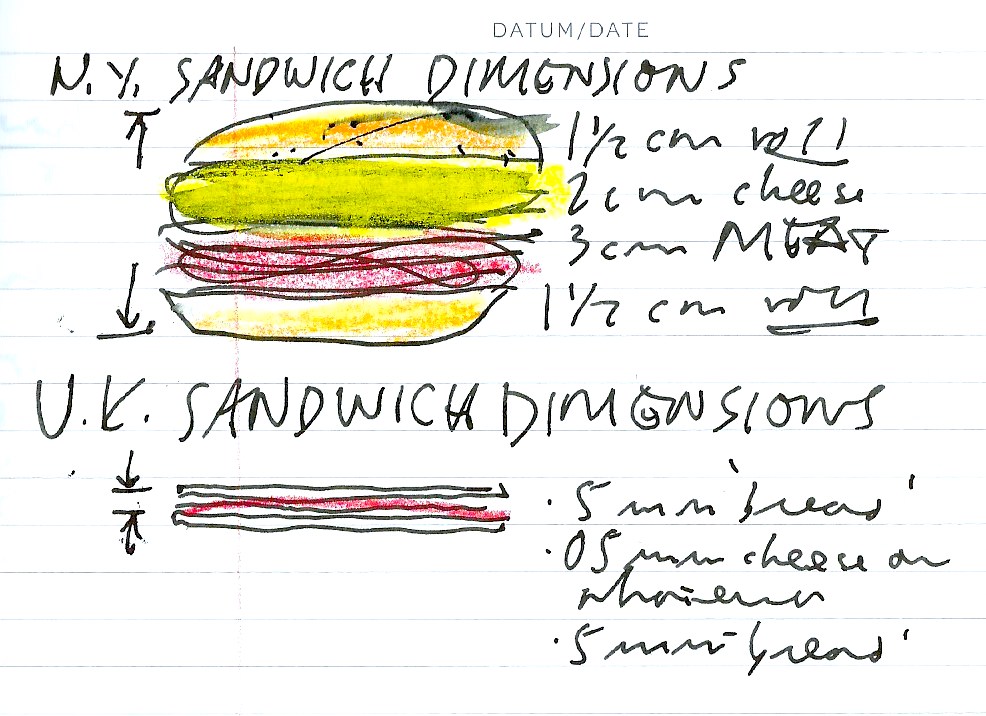

Wolf’s. Drawing by Todd McEwen.

WOLF’S: “Every Meal a Memory,” it said on the matchbook.

We liked to walk around Midtown. She favored the east side for its boutiques and galleries, while I favored the west side and its theaters, broadcasting companies, beer, and tobacco shops, which she didn’t give a damn about, though she was nice about it. She bought me an avocado-green sake bottle to put my pipe cleaners in.

Wolf’s wasn’t kosher. They had everything: all kinds of bread, meat, fish, cheese, no problem. The sandwiches were about eight inches high. I had consumed a number of them during the course of our romance, but one day my attention was arrested by the sight of a CHEF’S SALAD on the arm of a waiter. From that day on, all I ate at Wolf’s were these chef’s salads: two kinds of lettuce, Swiss cheese, cheddar, even a little scoop of farmer cheese; batons of ham, turkey and tongue, tomatoes, radishes, black and green olives, hard-boiled eggs, cucumbers, carrots, the whole drenched with “bleu” cheese dressing or Thousand Island and topped with the dill, dill, DILL of the seventies. Where has it gone?

One day we were feeling cozy and happy in Wolf’s—I say cozy but really it was a very hot day, so we were feeling reverse-cozy in the blast of their really powerful air-conditioning. I had my chef’s salad and Heineken, she her blini and iced tea. And in the icy coziness, talking, laughing, she relaxed and put her feet up on the empty chair opposite her. But this waiter passing our table looked down at her and said, “Miss! Please!” Now, this was a very well-brought-up, ladylike girl. And she blushed. Deep. And after that I wasn’t so keen on Wolf’s. And their subsequent history was checkered: the place started getting regular red flags from the health department. An altercation between kitchen workers ended in a stabbing.

But perhaps their troubles really began the day I deserted the sandwich for the salad.

Todd McEwen is the author of several novels including Who Sleeps with Katz and The Five Simple Machines, and Cary Grant’s Suit, a book about the movies. He lives in Scotland.