REHOBOTH BEACH, Del. — Standing outside Joe Biden’s church in this seaside town, the Rev. William Cocco mulls a question the president has grappled with over his long political career: How does a practicing Catholic defy church teaching and come out in favor of abortion rights, as Biden has done?

“I think it’s very difficult to reconcile that,” Cocco said in an interview this month after he presided over a service at St. Edmond Roman Catholic Church. “Life is a gift from God.”

Biden would have been at Mass that day, lining up for communion with the other parishioners, but he hurried back from his vacation home for meetings about Iranian plans to attack Israel.

An irony of Biden’s final campaign is that one of the most vexing issues he has ever confronted personally — abortion — is now central to his political survival. Biden’s campaign and his entire party have made abortion a defining issue in his re-election bid, hoping to rally female voters alarmed by Republican efforts to roll back reproductive freedoms.

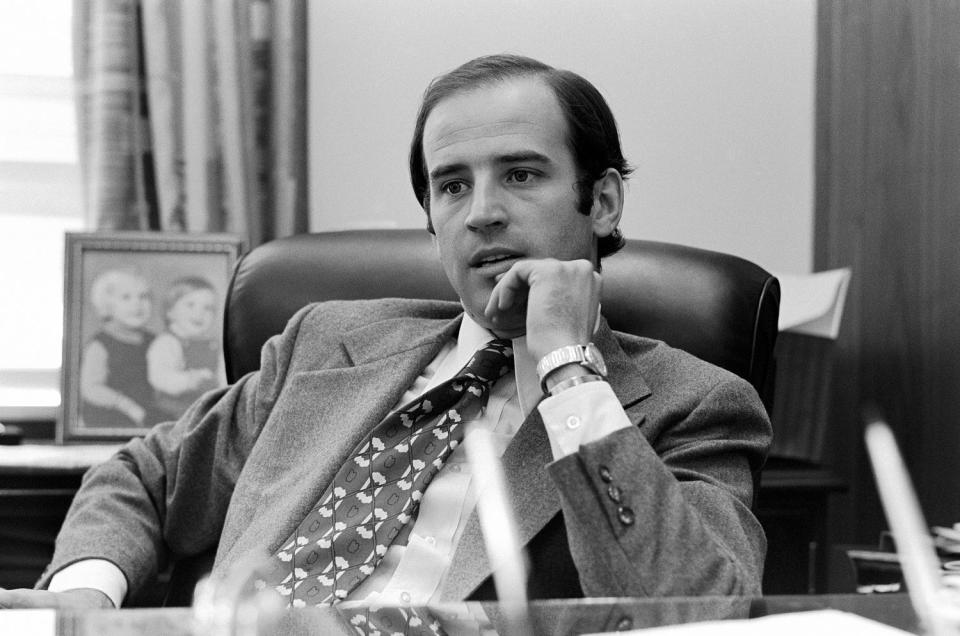

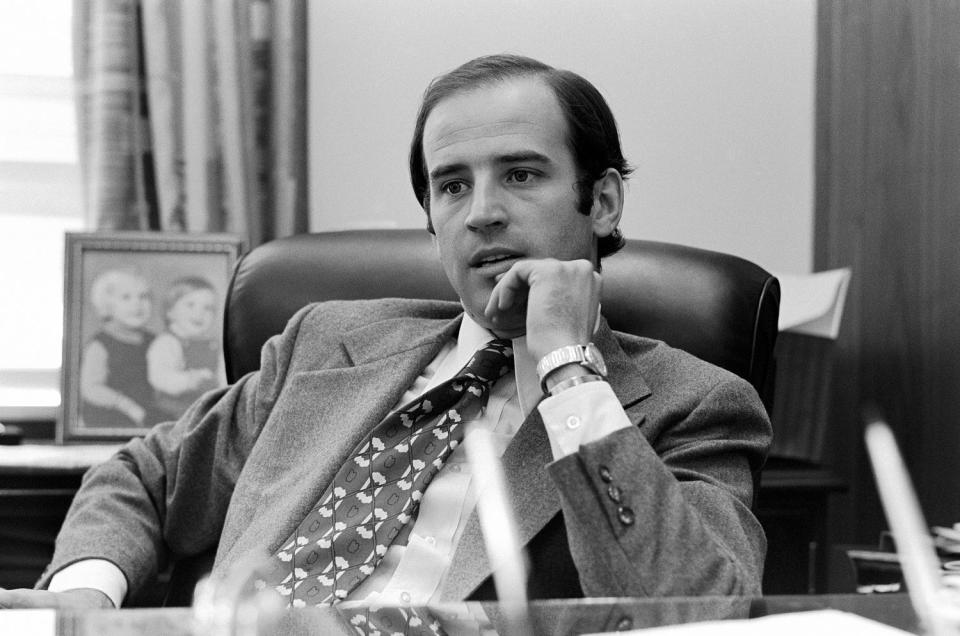

The young Catholic politician who once said the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade ruling that safeguarded abortion rights “went too far” — and who to this day remains uneasy with the procedure — is casting himself as the only thing standing between women and strict national abortion bans.

He vows to chisel Roe’s protections into law if he’s re-elected and secures friendly majorities in Congress, quashing a GOP-led push to forbid most abortion procedures. On Tuesday, Biden is scheduled to give a speech in Tampa, Florida condemning the state’s new six-week abortion ban.

Jennifer Klein, director of the White House’s Gender Policy Council, recalls Biden’s reaction upon hearing that the Supreme Court had overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022.

Thinking through the decision in the Oval Office, “he was angry,” Klein said in an interview. “He went quickly to the fact that this had never been done before and the Supreme Court had never overturned a fundamental freedom. He also went immediately to what might come next: If they take away this right, what other rights would be under attack?”

Biden may have little choice but to put abortion rights front and center. He is running about even with Donald Trump in the polls, despite Trump’s myriad legal troubles. Voters largely don’t know about Biden’s legislative victories, nor do they credit him with strong economic growth, opinion surveys show.

Biden needs something to jolt the electorate and galvanize voters who may feel his candidacy is uninspiring. Many allies see abortion as the answer. Polls suggest that voters already trust him on the issue. Asked which of the two candidates is closer to their views on abortion and same-sex marriage, 48% of registered voters in Pennsylvania — a key swing state — chose Biden, compared with only 35% who picked Trump, a Franklin & Marshall College poll this month found.

Hoping to ensure women retain access to abortion and, as a bonus, juice voter turnout in November, Democrats have been filing ballot measures that would enshrine abortion rights in Arizona and other battleground states. And Biden’s campaign has gone all in, churning out ads, news releases and social media posts casting him as a stalwart defender of the abortion-rights movement.

Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker, a Democrat who has pushed reproductive rights as a top issue in his state and founded a nonprofit group that is supporting abortion referendum efforts in multiple states, predicted abortion could “absolutely” decide November’s election.

“There’s a strong portion of the Biden coalition that is motivated on the issue and a strong group of people who might otherwise have stayed home but for the fact that the Dobbs decision [overturning Roe] came down and now this is a major threat to people all over the country,” Pritzker said in an interview.

Biden’s 50-year evolution from Roe skeptic to Roe adherent mirrors that of many Americans and the Democratic Party itself. The party’s presidential platform in 1972 — the year Biden was first elected to the Senate — carried not a single mention of abortion. By 2016, the year Hillary Clinton was the party’s nominee, the platform was chockablock with vows to defend abortion rights to the hilt.

The issue has been particularly fraught for Biden, an 81-year-old steeped in Catholic teachings and reliant on religious faith to cope with unthinkable tragedy: the deaths of two children and his first wife, Neilia.

“One of the things that carried him through his numerous difficulties is his Catholic approach of giving yourself to the Lord,” said Ted Kaufman, a longtime Biden confidant and his former Senate chief of staff.

On a human level, Biden has never fully overcome his misgivings about abortion. That’s evident even in the language he occasionally uses. Two years ago, talking to reporters before he boarded Air Force One, Biden referred to the procedure as aborting “a child” rather than a fetus, a clue about the point at which he believed life began.

Still, his stance is that he won’t impose his personal views on Americans who believe differently. In 1974, the year he said in an interview that Roe. v. Wade went “too far,” he also voiced opposition to a constitutional amendment to ban abortion, albeit with some ambivalence, a hometown news report at the time shows.

A column in the Morning News of Wilmington in January 1974 said Biden told a group of anti-abortion activists: “I am not sure my stand against such a constitutional amendment is right, nor am I sure the anti-abortionist stand is right, but right now I think I am more right than you are.”

Lauren Hitt, a campaign spokesperson, said in a prepared statement: “Joe Biden has opposed abortion bans since the 1970s. As a senator, he voted repeatedly to protect Roe, and as President, he has used his full executive authority to fight back on extreme MAGA attacks on reproductive freedom.”

Biden described the tensions between faith and policy last year at a Maryland fundraising event.

“I happen to be a practicing Catholic,” he said. “I’m not big on abortion. But guess what? Roe v. Wade got it right.”

A look at his record shows that his path has had its share of starts and stops. As a senator in 1982, he voted in a committee meeting in favor of a constitutional amendment that would have given states the power to restrict abortion if they chose, effectively overturning Roe v. Wade.

At the time, Biden said his aim was to push the vote to the Senate floor, where it would finally be resolved. The measure never got that far, and when it came up again the next year, he voted against it.

In 2019, as the Democratic front-runner for the presidential nomination, he reversed his long-held position in favor of the so-called Hyde Amendment banning federal funding for abortions.

That about-face came at head-spinning speed. One day, his campaign said he supported the Hyde Amendment; the next day, amid blowback from fellow Democrats, he dropped that position. He justified the switch by saying he could no longer support the policy because Republicans were restricting access to abortion in poor neighborhoods.

“Joe Biden is an Irish Catholic kid from Scranton,” said John Carr, founder of the Initiative on Catholic Life and Social Thought at Georgetown University. “He seems to stay with Catholic orthodoxy until he thinks the political or other costs are too high.”

Biden recognized early on that his nuanced position — wary of abortion at his core, accepting of abortion rights in the public square — was bound to cause him grief. He told fellow Sen. Abe Ribicoff of Connecticut in 1973 that his stance would most likely please no one, according to his 2007 memoir, “Promises to Keep.”

That proved prescient.

In Biden’s first year as president, conservative Catholic bishops argued that he shouldn’t receive communion given his backing of abortion rights. He met privately with Pope Francis at the Vatican in October of that year, and afterward he said the pope had assured him that communion shouldn’t be withheld.

Kathleen Sebelius, who was health and human services secretary in President Barack Obama’s administration, said in an interview that she sympathized with Biden’s predicament.

“I’m born and raised Catholic and went to Catholic schools for 17 years of my life,” said Sebelius, a former governor of Kansas. “I understand this issue. I’ve been called out by the archbishop. I was ordered not to take communion.

“I’ve been on the personal side of this and the political side of this, and I understand the struggle that those of us who are raised in a faith community and then live in a political world deal with,” she added. “It’s not easy. I think Nancy Pelosi [the former House speaker, who is also Catholic] understands that. I think Joe Biden understands it. It’s not a simple choice.”

Whatever Biden’s journey, most advocates say they now have full confidence that he is a reliable champion of abortion rights. When Biden left the Senate in 2009, he had a 100% rating from what was then called NARAL Pro-Choice America, a group promoting abortion access.

“Biden is not the same man as he used to be when it comes to abortion rights,” said Ilyse Hogue, former president of the organization. “I don’t think he’s been hiding his agenda just to win a second term and then secretly plans to turn around and become this anti-choice guy. I’m not worried about it at all.”

Some still don’t believe Biden goes far enough to promote reproductive rights.

Renee Bracey Sherman, founder and a co-executive director of We Testify, an abortion rights advocacy group, said Biden should use his megaphone to remove the stigma tied to abortion instead of airing his personal doubts. She pointed to recent surveys indicating that 6 in 10 Catholics support abortion rights.

“He’s the president of the United States; he’s not the pope of the United States,” Bracey Sherman said. “I’m sorry, he’s allowed to have his personal feelings. But at the end of the day, he is the president, and he is supposed to defend the Constitution and people in this country who need abortions.”

Bracey Sherman said her organization reached out to the Biden administration multiple times offering to bring Catholics who have had abortions into the White House to share their stories — but has yet to hear back.

“He makes it seem as though he’s the one who’s following the Catholic teachings,” she said. “But what about the rest of the Catholics in America who do support access to abortion and have abortions?”

Elections are a choice. Even Biden detractors say they’re fully aware that the only realistic alternative at this point is Trump, whom they view as an extremist on the issue.

Abortion looks to be one of Trump’s glaring vulnerabilities. He has boasted about his role in overturning Roe v. Wade through his appointment of three conservative Supreme Court justices during his single term.

“There is a fundamental question and a fundamental difference between the president and Donald Trump and their belief on whether the Constitution affords women a right to choose. Donald Trump does not; Joe Biden does,” said Kate Berner, a former Biden White House official.

Trump recently said abortion decisions should be left to the states after he was criticized that he has been murky about what he believes. Even so, he sought to dissociate himself from a recent state court ruling in Arizona upholding a 19th century law imposing a near-total abortion ban.

Disavowing Arizona’s strict anti-abortion measure isn’t so easy for Trump. The reason it can take effect springs directly from the votes of conservative Supreme Court justices whom Trump worked to install.

“The fact is that he announced he was going to stack the court with justices who could be counted on to overrule Roe v. Wade,” said Laurence Tribe, a Harvard Law School professor emeritus. “He succeeded in that. They did it. That led to the revival of laws like Arizona’s, even if Trump says: ‘Oops, I’m sorry that’s the consequence. It doesn’t make me look good politically.’”

Biden was at the White House last Sunday, dealing with the fallout from Iran’s attack on Israel. When he’s in Washington on the weekends, he’ll often attend services at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Georgetown, the church frequented by the nation’s first Catholic president, John F. Kennedy. A Black Lives Matter banner hangs from a fence outside.

Biden wasn’t in the pews that day; he was attending a virtual meeting with U.S. allies about the Iranian attack.

The Rev. Patrick Earl led the Mass and greeted congregants at the doorway afterward. He said in an interview that Biden is a “good presence” during services, recalling how he once left his seat to congratulate a boy’s family celebrating his First Communion.

Earl said he understood Biden’s position, even if it conflicts with church teaching.

“As the political leader of a very varied country, you can’t just say, ‘You’ve got to believe as I believe,'” he said. “You just can’t.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com